Improved Web App Performance through Optimized Hardware Usage

Web applications can be developed in many ways. However, not all performance optimizations are considered that are necessary to meet the growing performance expectations. Especially when compute-intensive services are to be offered, powerful servers provide advantages. But when it comes to transferring data to the client, latency is often the limiting factor. Our goal is therefore to weigh up: Is a powerful server worthwhile, or does optimized client code deliver better performance?

Disclaimer: All graphics are self-created and serve to illustrate the topic. The graphics are simplified and do not represent the exact complex functionality.

Example Application: Image Compression Let's imagine a simple application that compresses images. Smaller data volumes mean shorter transfer times and thus a faster loading web experience. The basic concept:

- Upload: The user uploads one or more images.

- Processing: Using libraries or canvas techniques, for example, a JPEG is compressed.

- Download: The compressed image can then be downloaded.

JavaScript Performance and Its Limitations It is well known that web applications are often affected by the limitations of JavaScript – a language that runs in modern browsers via engines like V8 (Chrome), SpiderMonkey (Firefox), or JavaScriptCore (Safari).

The Code Execution Process:

- Parsing: The source code is converted into an abstract syntax tree (AST).

- Interpretation: An interpreter reads the AST and translates it into bytecode that can be executed by the engine. This step is relatively fast but results in less optimized code.

- JIT Optimization: Frequently used code sections ("hot spots") are converted into efficient machine code.

Challenges:

- Runtime Overhead: The dynamic nature of JavaScript leads to additional overhead compared to pre-compiled languages.

- Single-Threaded: Since JavaScript typically runs in a single thread, parallel processing is limited.

- Garbage Collection: JavaScript uses automatic memory management. The garbage collector can lead to unexpected performance drops as memory cleanup occurs unpredictably.

How Can We Improve Our Application Step by Step? End devices are getting better and better, and it's nothing new that web applications in their basic form don't really utilize the hardware. This is exactly where we start: Through targeted optimizations, we can improve the performance of our application step by step. It starts with optimizing the JavaScript code itself - but that's what we have OpenAI, DeepSeek, and others for -, continues with efficient use of browser APIs, and ends with the integration of technologies like WebAssembly, WebGPU, etc., which enable compute-intensive tasks to be executed much faster. In the following, we want to look at which specific web technologies we can use in our project to get the best out of our web application.

Our example application is kept very simple, so there isn't necessarily anything we need to do right now, but as we extend it, significant performance problems quickly arise. We allow the user to upload not just a single image, but as many as they want.

Here the problem of the single thread becomes immediately apparent. Because in this case, we have to compress each image one after another. But there is the first solution to escape the limitations of the main thread. Enter Web Workers.

Web Workers are a simple web solution that allows JavaScript code to be executed in separate background threads. These threads run parallel to the main thread, allowing tasks to be offloaded without affecting the user interface.

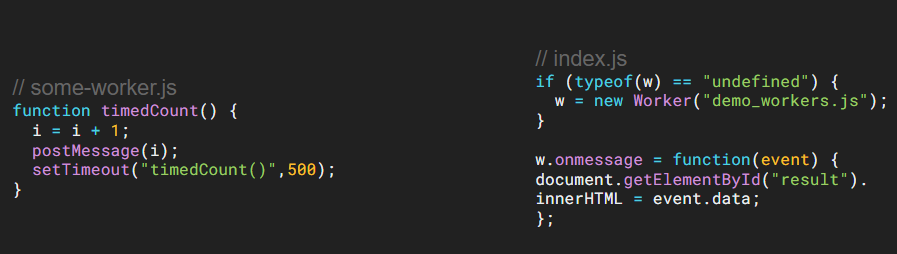

As shown here, Web Workers are very easy to integrate. You create a JS file

that executes some code, here as an example a counter with timeout. If we

executed it directly on the main thread, it would block most other activities.

But if we call the file with new Worker, we start another thread on which our

counter runs. Between the threads, we communicate in both directions with

onMessage and postMessage. In this case, the main thread receives a message

every 500ms and acts accordingly, but is not blocked by the timeout. For our

example application, this means that we first check how many threads the client

has available and start an appropriate number of Web Workers for our

application. So we can work with 4 threads, for example. Put the uploaded images

in a queue and let the threads process them one by one, without our UI and user

interaction being affected.

Now we have parallelization built in, which can make our application x-times faster through parallelization, depending on how many threads we can sensibly use. But this doesn't change the speed of individual tasks - they still have JavaScript overhead. We also notice that when we convert to different image formats to compress better, it takes even longer, or we can't find libraries that can decode and encode certain image formats.

Here comes another excellent technology that solves or improves many of our problems, but makes implementation a little more complex or even possible in the first place. In image and video processing, there are countless algorithms, but most are written in native languages like C++ and Rust and often have no JavaScript counterpart. This is where WebAssembly, or WASM for short, helps us.

WASM is a bytecode format that can be executed in web browsers. It enables cross-platform use of native code performance in web applications. It serves to execute compute-intensive operations, which can be better optimized outside of JavaScript, in the respective languages at near-native speed.

We can now use WASM to achieve several things:

- The code is already compiled and optimized, so it's inherently faster than what we can achieve with interpreted JavaScript.

- We can use any language that offers a WASM compiler.

- Access to appropriate libraries from other languages.

- Through WasmGC, the garbage collection of the compiled language itself can be used.

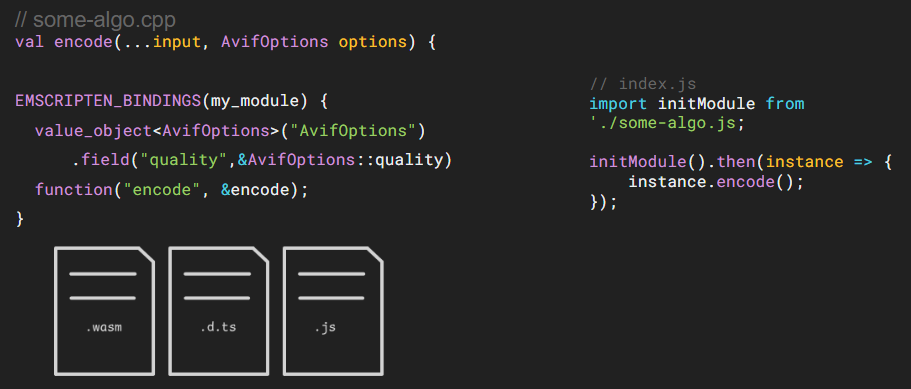

Let's take C++ as an example and write an encoder for the AVIF image format.

This allows for very good compression, which is why we definitely want to offer

it in our web app. Once we have written the C++ code in a callable function, we

can make it available to JavaScript code through EMSCRIPTEN

BINDINGS. This serves as an interface so that when we compile the code, it's

clear how JavaScript can access what. TypeScript types can even be created if

desired. The result is a .wasm file (the compiled code), a type file (if

desired), and a JavaScript file to access the WASM file. Once we instantiate

the JavaScript file, we can call the encode function from it. We can do this

directly from our Web Workers, so we have both parallelization and better,

faster, pre-compiled code.

So let's move on to the next step. Nowadays, everything is somehow connected to AI. And why shouldn't our application participate too? Whether we want to offer another feature that requires an AI model, such as background removal, or there are simply AI compression models that we want to offer.

But when we talk about AI, we immediately think of graphics cards, and we currently only run our code on the CPU. Now that we've reached the point where we want to use code that is simply meant to run on a GPU, our current setup is of no use. So let's move on to another hardware interface: WebGPU.

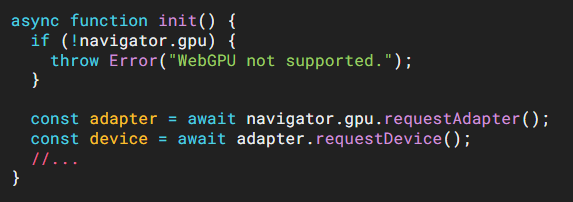

WebGPU (WebMetal on iOS) is a successor or alternative to WebGL in the style of native GPU APIs like Khronos Vulkan, Microsoft's DirectX, and Apple's Metal. It enables the use of features from modern GPUs in the browser and was developed with W3C. Chrome has supported WebGPU since version M113 (May 2, 2023), but there is still a lack of stability and resources to be actively used by JavaScript libraries. TensorFlow.js, for example, already offers the option to use WebGPU if possible.

In general, standalone usage is a bit more complicated here, but it's excellent when using AI libraries like TensorFlow.js. It's important to check whether WebGPU is already supported, as there are still numerous browser versions or old devices that don't (yet) support it. Then you get the adapter and GPU access and can work with shaders, for example, and perform complex matrix calculations.

To complete the journey with AI and hardware access, let's look at what the future holds. So let's go one step further and consider the possibilities in the machine learning domain with neural networks.

Like WASM and WebGPU, WebNN also provides an abstraction layer to hardware.

The Web Neural Network API defines a web-friendly, hardware-agnostic abstraction layer that leverages the machine learning capabilities of operating systems and underlying hardware platforms without being tied to platform-specific capabilities. The abstraction layer meets the requirements of major JavaScript machine learning frameworks and enables web developers familiar with the ML domain to write custom code without the help of libraries.

Evaluation

| Technology | Emoji | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Web Workers | 😊 | Multithreading |

| WASM | 🤓 | Complex libs, bypass interpreter |

| WebGPU | 🥵 | GPU access, AI models & animation (WebGL alternative/successor) |

| WebNN | ⚒️ | NPU access, neural networks, AI accelerator |

Conclusion and Outlook The journey from the traditional browser environment to optimal use of modern hardware shows: Through targeted, cross-technology optimizations, the performance of web applications can be significantly improved. The key is always to find the right balance between server-side and client-side processing and not to increase complexity beyond what is necessary. Future developments, such as smaller AI models or further optimizations through WASM, will continue to make this balancing act easier.

Further questions that go beyond the scope of this article include:

- How much do we need to consider older devices?

- Is offloading services to the client worthwhile compared to server solutions?

- How does internet speed affect the need for powerful end devices?

- Is a minimal JavaScript approach beneficial in the long run?